1994 - 1997

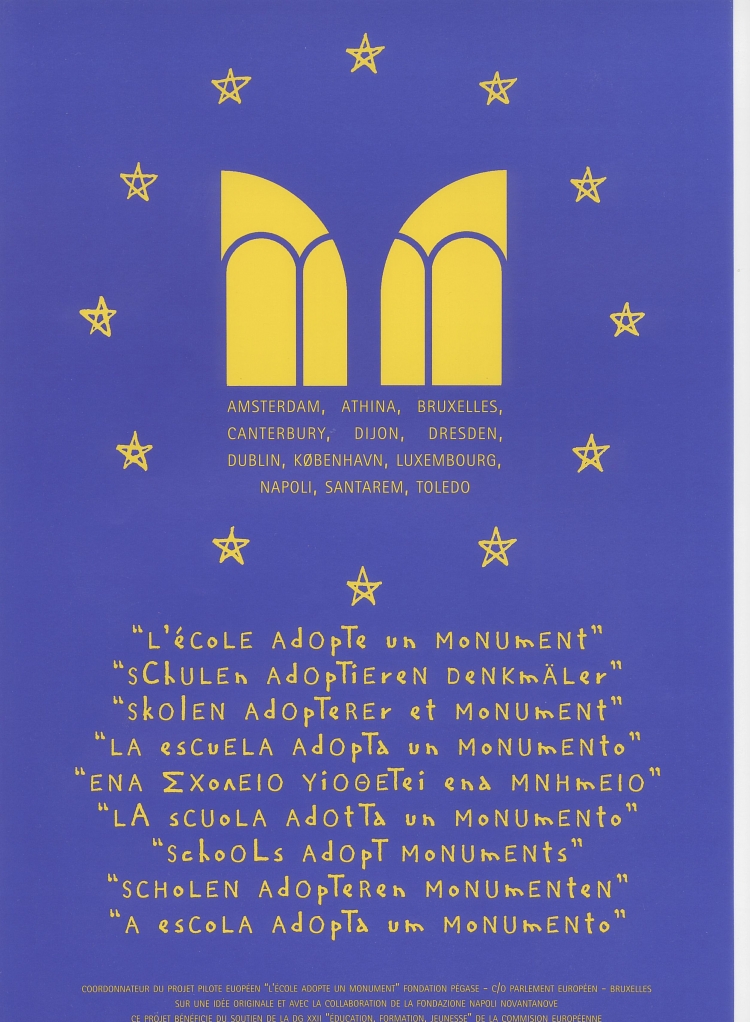

The Schools Adopt Monuments project was born in Naples as part of the Fondazione Napoli Novantanove's general strategy. This Foundation has, since 1992, aimed at stimulating awareness of the importance of knowing, safe guarding and promoting the local cultural heritage, not only among the general public, but mostly within and through schools.

The project was launched together with the first edition of the Foundation's Open Naples Monuments' Doors festival and has been explicitly and minutely designed and developed with the Foundation's educational (especially lifelong learning) aims in mind.

The social and educational impact enjoined by the experiment was such that the Foundation was prompted to prepare a set of tutelary Regulations and the project then spread from Naples to the rest of Europe under the auspices of the Fondation Pegase.

The success of the Schools Adopt Monuments idea has been literally overwhelming, but what is even more extraordinary is the unwaning enthusiasm and active involvement still shown well into the project's 4th year, by the 160 schools currently involved.

An appropriate way of reviewing these past four years might perhaps be to quote the reasons given by various schools for their joining the project. They contain important clues to understanding the attitudes of the young towards their cultural heritage. These are mainly social in nature.

Schools adopt monument because they want "to repossess everyday space, where it is so important to find ways of living in harmony with the things around us", "to be involved with the outside world and explore the resources to be found in real life", "to understand our roots and build our identities , to bring back to life a monument which had been cancelled from our historical memory and from the urban landscape".

These last two comments come from schools in degraded peripheral areas of Naples and allow a glimpse not only of the depth of the problems facing teachers, but also of the great hope invested in the action of schools there. Indeed, these areas see the adoption project as nothing less than a vehicle for their rehabilitation. Local monuments have come to represent, then,extraordinarily efficient means for concretely enacting solidarity, social involvement, the sharing of responsibility, and one's search for roots and meaningful relationship with people and the environment.

One must mention some particularly significant participants: for example, a school for the blind made a clay model of a church facade and thus "saw their environment with their hands". The adoption project, as they put it, symbolically and concretely place their local church, their object of study, into their' own hands.

In yet another school, a technical college, the adoption project had an effect on their work and teaching methods. They mention how they have been able to give their students different ways of reading their urban environment by combining an analytical objective approach with their subjective, affective attachment to their local environment, and they comment that one needs to work at "educating students to live their city as a place of memories and of life"; "developing individual potential through cooperation rather than through competition of ; "raft* sing the quality of communication through the acquiring of new codes"; 'fostering critical analysis and sensibility by developing awareness of the existence of different point of view".

The project of adoption of Church Santa Maria dell'Incoronata by the lower secondary school Grazia Deledda in Naples has been extremely successful and satisfactory. Understanding how meaningful a formal commitment such as adopting a monument is and realising how many valuable opportunities of heritage education are offered, have been the

keys to success. Teachers were aware they were taking part in an exceptional educational experience to be performed on site, in direct contact with the monument and the institutions in charge of it, and they focused their work on the study of the monument adopted.

The two key-terms of the project - to know and to safeguard - were made concrete thanks to a series of research works and actions.

Education and civil commitment.

The enthusiasm of the students about the adoption was never stifled nor disappointed. By studying the monument in such a thorough and creative way, their interest increased and they sought to let others share the results and the materials produced. Many difficulties had to be overcome to attain such a goal, and to communicate with and raise the interest of people of any cultural level, scholars and experts included. They were successful in their stubborn appeal to draw the attention of public opinion and their demands or suggestions to the authorities for appropriate interventions that would make the monument more accessible. Today the monument is more visible and respected, as well as protected. These results, the appreciation by the public authorities and experts, gave the students a sense of self fulfilment and pride. The schools attained their goals of contributing to the common interest and increasing self-esteem thanks to an

extraordinary idea that helps schools perform their mission: the development of the personalities of the citizens and their awareness of the outside world. As a token of the project's success, the students who are now in high school continue attending all the events and express a genuine interest in the monument and in the cultural and artistic heritage of their city as a whole.

All rights reserved: photographic archive, texts and translations.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, ARCCORDING TO INTERNATIONAL LAWS AND CONVENTIONS.

Nessun materiale può essere riprodotto senza autorizzazione.